back to all news

back to all news

Pee-cycling for the future: Addressing global change with urine-derived fertilizer

Will Brinkerhoff is a second-year PhD student in Associate Professor Jennifer Blesh’s Soil and Agroecosystems Lab at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability (SEAS).

On most midwestern croplands, farmers apply large amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus, which cause nutrients to “leak” into the surrounding environment. Strong evidence suggests that recoupling nutrient and carbon inputs, by applying organic nutrient sources like compost, can reduce nitrogen and phosphorus losses that harm freshwater systems and produce greenhouse gas emissions. If farmers could recycle large amounts of “wasted” nutrients from food waste and human waste and apply them to croplands, it could drastically reduce demand for energy-costly synthetic fertilizers.

One of my projects aims to understand how two important sources of recycled nutrients—compost from food waste and urine-derived fertilizer (UDF) from human urine—can improve nutrient retention and circularity in the food system from field to regional scales. Both of these nutrient sources encourage nutrient recycling between urban and rural environments, and applying them together could enhance nutrient retention in farm fields, reducing leaching and gaseous losses. In this project, urine was collected from a source-separating toilet and was pasteurized and concentrated into a high-quality fertilizer product. One of these source-separating toilets can be found in the G.G. Brown Building on North Campus, in the same building where U-M Professor Nancy Love’s research group studies urine-derived fertilizers.

One of my projects aims to understand how two important sources of recycled nutrients—compost from food waste and urine-derived fertilizer (UDF) from human urine—can improve nutrient retention and circularity in the food system from field to regional scales. Both of these nutrient sources encourage nutrient recycling between urban and rural environments, and applying them together could enhance nutrient retention in farm fields, reducing leaching and gaseous losses. In this project, urine was collected from a source-separating toilet and was pasteurized and concentrated into a high-quality fertilizer product. One of these source-separating toilets can be found in the G.G. Brown Building on North Campus, in the same building where U-M Professor Nancy Love’s research group studies urine-derived fertilizers.

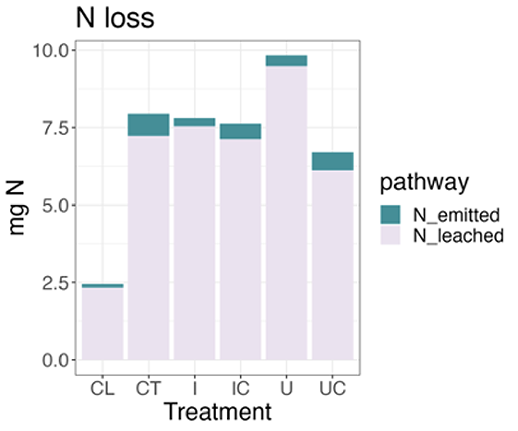

As a component of my dissertation research, I conducted a greenhouse experiment at Matthaei Botanical Gardens over the summer with collaborators from U-M’s Civil and Environmental Engineering department. My team applied different fertilizer treatments, including compost and UDF, to a brassica crop planted in conventional farm soil from Michigan. I used a wide array of metrics to assess how the different fertilizer treatments affected soil health, with a focus on processes that build soil carbon and drive nutrient conservation or loss. Because many of these processes are carried out by soil microbes, the analysis includes identifying whether the composition and function of the microbial community changes with the different fertility sources. My team also measured nitrogen losses through leaching or emissions of nitrous oxide—a potent greenhouse gas—from the soil in each treatment. For these methods, we sealed each plant in a five-gallon bucket and extracted gaseous samples from inside the chamber over an hour to quantify the gaseous emissions produced by soil bacteria in each treatment. By identifying how soil health metrics differ for each fertilizer type, this project provides preliminary evidence to understand the potential for UDF and compost, applied alone or together, to help mitigate agriculture’s impacts on global change.

Results from this greenhouse experiment will be collated into a journal article and used to inform a nutrient flow analysis for lower Michigan that a larger collaborative U-M team is conducting (including PhD students at SEAS, the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, and Engineering). This larger group will extrapolate findings to larger agricultural landscapes across Michigan. Overall, this study is producing important insights on opportunities for expanding the use of novel, more sustainable agricultural practices to alter global change trajectories.

This project was made possible through funding from U-M’s Graham Sustainability Institute and the Institute for Global Change Biology at SEAS.