back to all news

back to all news

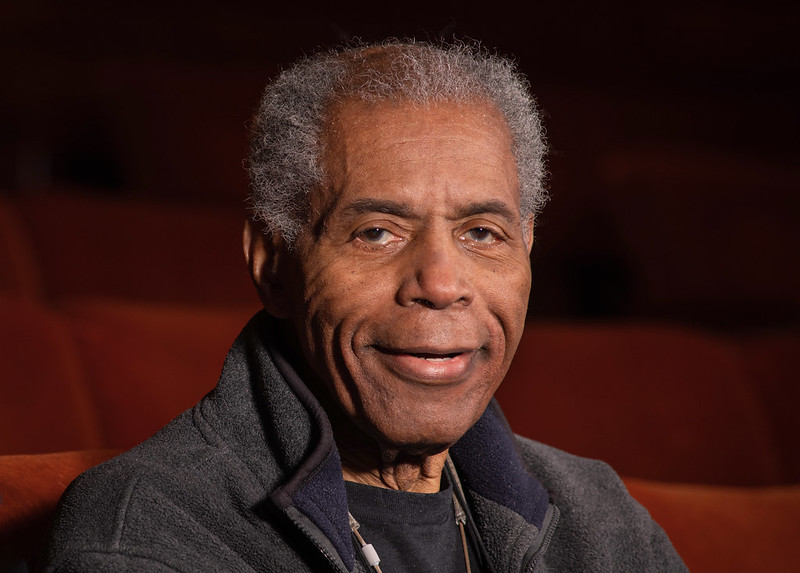

In memoriam: Bunyan Bryant (1935–2024)

Bunyan Bryant, a pioneer in the field of environmental justice and a beloved professor at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability (SEAS) who for four decades shepherded and inspired thousands of social and racial justice advocates, died peacefully at home in Ann Arbor on March 28, 2024, after a short battle with cancer. He was 89.

Jean Rae Carlberg, Bryant’s loving companion of 63 years and wife of 31 years, was by his side.

Countless former students, colleagues, friends, and activists are mourning Bryant, who had a profound influence not only at SEAS, where he helped to establish the nation’s first environmental justice program, but on the broader environmental justice community, which continues to follow Bryant’s lead of advocating for people of color and marginalized communities that are fighting against systemic racism and environmental hazards.

“The world has been a better place with Bunyan’s vision, determination, compassion and involvement,” said SEAS Professor Paul Mohai, Bryant’s longtime friend and collaborator of more than 30 years. “He had a deep compassion for other people and humanity at large, and I will miss him greatly.”

“Bunyan’s legacy of advancing environmental justice will not be forgotten,” added SEAS Dean Jonathan Overpeck. “For more than four decades, Bunyan taught and mentored SEAS students, modeling for them how to be effective advocates for equity and justice in communities that face environmental racism. Thanks to Bunyan’s tireless passion for creating change, his legacy as an environmental justice pioneer will live on in future generations of advocates.”

Bryant joined SEAS in 1972 and was the first African American professor on the faculty. Known then as the School of Natural Resources (SNR), Bryant and SEAS Professor Emeritus and Dean Emeritus James Crowfoot were recruited to begin the school’s Environmental Advocacy Program, a student-driven initiative that blended environmental courses with social justice activism. It later became the Environmental Justice program in 1992, the first program of its kind in the nation to offer undergraduate and graduate degree specializations.

In his 2022 memoir, “Educator and Activist: My Life and Times in the Quest for Environmental Justice,” Bryant noted that he “knew nothing about natural resources or the environment, nor was he interested in these topics.” Still, his interest was piqued enough that he decided to give a presentation to students and faculty as part of the interview process.

“We were being asked to build from scratch a program unlike any other program in the nation; there were no models to emulate,” Bryant wrote in his memoir. “Sometimes, I thought it would be exciting to be a trailblazer in uncharted waters, while at other times, I felt it was foolhardy because the probability of failure would be higher than average. I’d also heard there had been quite a heated discussion as to whether environmental advocacy belonged in the school. It was not just me as an individual who was at issue, but also the program that Jim and I were hired to build.

“Nonetheless, I accepted the offer to join SNR,” he added. “Thus began a 40-year academic connection that would change my life forever.”

Born on March 6, 1935, in Little Rock, Arkansas, during the Great Depression, Bryant grew up in a loving, close-knit family in a “Black neighborhood sandwiched between two white communities.” Though Bryant described a somewhat idyllic childhood in his memoir, he also noted there was a “world of dangers surrounding a young Black boy growing up in the American South in the 1930s and 1940s. And despite the best efforts of my family to shelter me, it didn’t take long for me to become aware of those dangers.”

As Bryant grew older, he began to see evidence of a segregated South that was visible everywhere—from posted signs that indicated “For Whites Only” or “Colored Served at the Rear” to “rules of subservience that a young Black male had to obey if he hoped to survive.”

Lured by the promise of better-paying jobs, Bryant and his family moved north to Flint, Michigan, in 1943, where, as part of the Great Migration, they sought better economic and social conditions. Bryant was 8 years old.

He graduated from Flint Northern High School and worked briefly at General Motors before earning a BS in social science from Eastern Michigan University. Bryant went on to earn two degrees from U-M: a master’s degree in social work and a PhD in education.

As a U-M student in the 1960s, Bryant became involved in civil rights activism—even filing a complaint with the Michigan Civil Rights Commission about a racially discriminatory housing policy after he was refused rental of an apartment unit in Ann Arbor—and befriended another activist, Jean Carlberg, who would later become his wife and lifelong partner. Carlberg is a retired teacher of history, mathematics and French who previously served on the Ann Arbor City Council and other commissions.

It was while completing his doctoral thesis at U-M’s School of Education that Bryant and his eventual collaborator Jim Crowfoot were approached about developing the curriculum for the Environmental Advocacy Program at SEAS, which would combine Bryant’s background in education, social work, and the civil rights movement with Crowfoot’s expertise in organizational psychology.

“Both of us were shaping our careers to be involved in processes of social change involving equity and justice,” Crowfoot recalled about he and Bryant’s beginnings. “We had worked together for a few years in a graduate student-led research and action group at U-M that was doing intervention work and research on reform in schools, particularly high schools in the United States. That’s how Bryant and I met each other and came to work together.

“As I look back on my career, the Environmental Advocacy Program was a life-changing opportunity, and core to it was my collaboration with Bryant,” added Crowfoot, who worked side by side with Bryant for 10 years before becoming dean.

“Bryant had an incredible vision about the potential for change, and he was a fantastic educator. He also had an incredible ability to collaborate and move forward under very trying circumstances. Certainly being the only Black faculty member in the School of Natural Resources at that time and for several years afterwards, was a tremendous act of courage and skill on his part. He kept working in innovative ways with students and constituencies beyond the university when his home base was anything but hospitable.”

The Environment Advocacy Program grew to national prominence under Bryant’s leadership and in partnership with Paul Mohai, another environmental justice scholar with expertise in quantitative research skills. Mohai joined the SEAS faculty in 1987.

In what Bryant called a “seminal year,” he and Mohai organized and led the groundbreaking 1990 Michigan Conference on Race and the Incidence of Environmental Hazards, held on the U-M campus that January.

Twelve scholar-activists, mostly people of color, were invited to present papers at the conference, which proved to be an “intense and electrifying experience,” according to Bryant. There were also participant observers from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Michigan governor’s office, the state departments of natural resources and public health, and Ann Arbor’s Ecology Center.

Two major outcomes resulted from the conference: Bryant and Mohai published “Race and the Incidence of Environmental Hazards,” one of the first major scholarly books examining the links between race, class and environmental hazards, and it led to the creation of the Office of Environmental Equity and subsequently the Office of Environmental Justice in the U.S. EPA.

“It was exciting to collaborate with Bunyan and see the amazing impact it had so quickly,” Mohai said about the groundbreaking conference, “including catalyzing conference participants to draft on the spot a letter requesting meetings with the heads of the U.S. EPA, the White House Council on Environmental Quality, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to inform them and prompt them to action.”

As a result, then U.S. EPA Administrator William Reilly met with Bryant, Mohai, and other key members of the Michigan Conference in September 1990. “Bunyan was superb in leading our group of eight (dubbed the ‘Michigan Group’ by the EPA) at the meeting and ensuring that there would be many more meetings to come,” said Mohai. “It was clear, with all his top staff present and the words the administrator spoke, that the EPA was going to do something significant to address and advance policy on environmental racism and injustice.”

The conference helped to legitimize environmental justice as an academic endeavor and contributed to President Bill Clinton years later signing Executive Order 12898 to address environmental justice in minority and low-income populations.

“Of course, the efforts of the Michigan Coalition didn’t solve the problems of environmental injustice that plague American society—not by a long shot,” Bunyan wrote in his memoir. “But we succeeded in getting those problems on the national agenda, which is an all-important first step toward addressing them.”

In 1990, another important milestone occurred for Bryant and Mohai when they were appointed faculty investigators of the U-M Detroit Area Study on Race and Environmental Hazards, the first survey research study at the time to study white and African American attitudes about environmental issues in the Detroit metropolitan area. It was also the first environmental justice analysis ever conducted in the metro area, examining the concentration of poor and African American residents around hazardous waste sites and polluting industrial facilities.

Bryant continued teaching at SEAS until his retirement in 2012, influencing countless students along the way, including Michelle Martinez (MS ’08), who is the inaugural director of the Tishman Center for Social Justice and the Environment at SEAS and an influential environmental justice advocate in Detroit.

“Bunyan provided a social and political framework for change through different kinds of participatory research,” Martinez said. “He labored to help students understand the long arc of leadership in marginalized communities. He took the time to explain how good healthy group dynamics enhanced our outcomes. He helped to advocate for us against those who sought to replicate some of the bad behaviors of the past. And he demonstrated what it looks like to be a good steward of knowledge and social change.

“I would not have known that environmental justice was a field without his influence,” she added, “nor would I have selected the professional path I have now without his guidance.”

At the time of Bunyan’s retirement, SEAS hosted a conference, “Honoring the Career of Bunyan Bryant: The Legacy and Future of Environmental Justice,” in recognition of his contributions to the field. He also returned to SEAS in 2020 when the school celebrated the 30th anniversary of the historic EJ conference Bryant helped to spearhead, which featured national and regional leaders in the EJ movement.

Bryant received numerous awards and accolades throughout his career, including the School of Natural Resources and Environment Outstanding Teaching Award in 2000 and later a promotion to the Arthur F. Thurnau Professorship. In 2004, he was the recipient of the Ernest A. Lynton Award for Faculty Professional Service and Academic Outreach. His advocacy also was recognized by his hometown of Flint in 2008 with the Lifetime Leadership Award and later in 2017, when he was presented the Environmental Justice Champion Award at the Flint Environmental Justice Summit.

Bryant remained connected to SEAS and closely followed its news and activities until his death. Ever the mentor, he was asked shortly after his cancer diagnosis if he wished to impart any final words of wisdom to the next generation of environmental justice advocates. He shared the following advice:

“Always be hopeful, because that is a source of energy that will enable and inspire your work and your vision for the future,” Bryant said. “With hope comes new visions and possibilities of social and environmental justice. Use the scientific and/or evidence-based knowledge that you have accumulated during your stay with us humbly and in concert with the people you are serving.

“And, take good care of yourself so that you can continue your work well into the future.”

A celebration of life for Bryant will be held on May 4, 2024, at 11 a.m. at First Unitarian Universalist Congregation, 4001 Ann Arbor-Saline Rd, Ann Arbor, MI. Family visitation will begin at 10 a.m.

To leave a memory and condolence, visit the obituary on MLive.